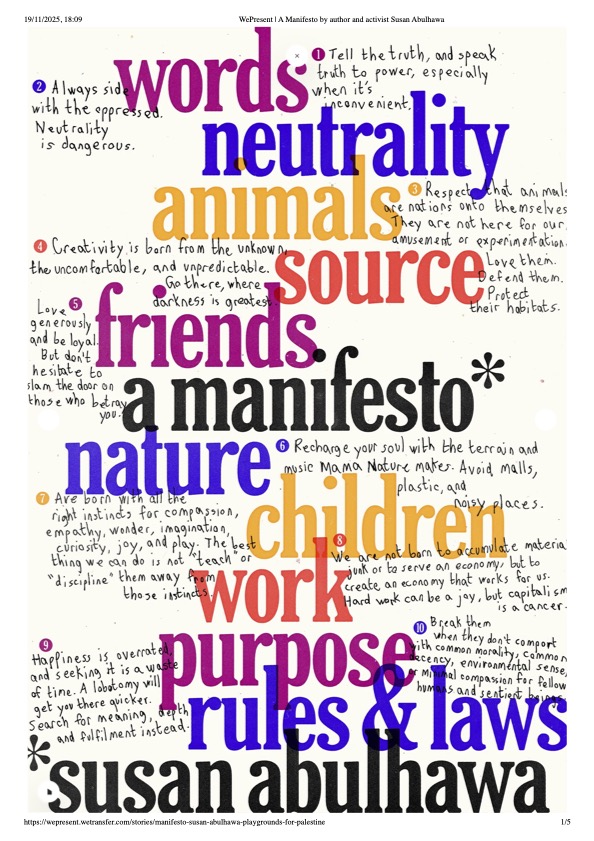

Ten rules for living by writer and founder of Playgrounds for Palestine Susan Abulhawa

Stewart Keller – Coloring Book

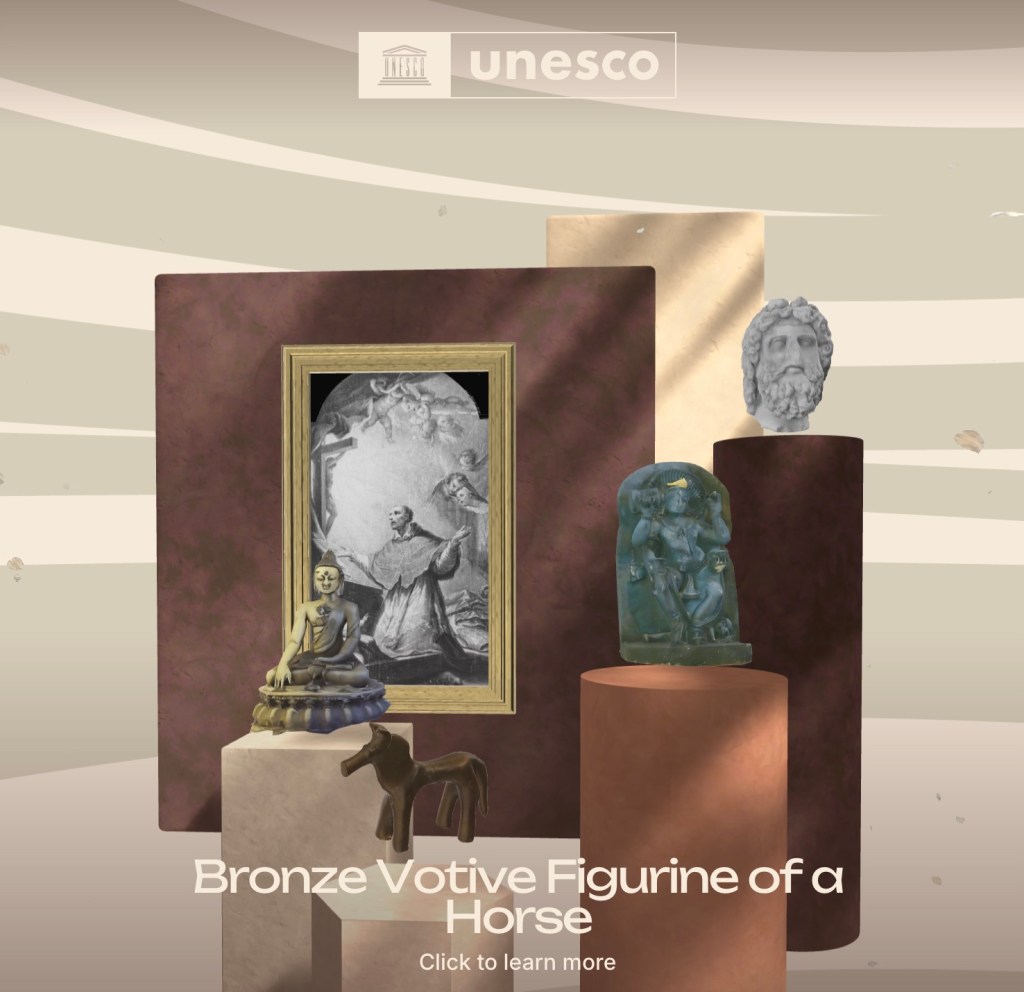

UNESCO has launched a virtual museum of stolen objects to draw attention to illicit trade in indigenous artefacts

UNESCO has launched the Virtual Museum of Stolen Cultural Objects, the first of its kind worldwide. 🌍

An immersive digital space that brings together over 240 stolen and missing cultural objects in 2D and 3D from 50+ countries — and the voices of the communities they were taken from. More than a museum, it’s a tool to:

- Raise awareness about illicit trafficking

- Support stronger protection policies

- Promote provenance research

- Foster cooperation for restitution

Created by Francis Kéré, Pritzker Prize-winning architect, with the generous support of Saudi Arabia and in partnership with INTERPOL. A milestone in the global fight against illicit trafficking of cultural property. On the International Day against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property, we’re reminded that protecting heritage means protecting our shared identity.

Ecofeminism in Contemporary Art: an Australian Perspective

Some of the most powerful contemporary art engaging with the ecological crisis is that which draws on ecofeminism’s non-dualistic thinking and the deep customary insights of First Nations knowledges. In this article I consider work by three contemporary Australian artists whose aesthetics help facilitate the sensory recognition of the interrelatedness of the human and more than human, including the inextricable histories of colonial violence and environmental degradation, and position art as an inclusive platform for ecological communication and activism.

Ecofeminist philosophy explores the connections between the instrumentalisation of nature, the control of women, and the acquisition of scientific knowledge, all of which underpin modernity and the ideology of “progress”. As early ecofeminist Carolyn Merchant argues, “Nature cast in the female gender, when stripped of activity and rendered passive, could be dominated by science, technology, and capitalist production”.1 Ecofeminism critiques male-biased Western canonical views about women and nature and seeks alternatives and solutions.2

In Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, philosopher Val Plumwood proposes that Western culture has been systematically unable to acknowledge dependency on nature, the sphere of those it has defined as “inferior” others. As a result, the master discourse of reason has distorted the knowledge of the world and developed “blind spots” that threaten our survival. It is only through creating “a truly democratic and ecological culture beyond dualism”3 that we can transition to a sustainable future. In Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason, she reaffirms that “developing environmental culture involves a systematic resolution of the nature/culture and reason/nature dualisms that split mind from body, reason from emotion, across their many domains of cultural influence”.4 While sharing with deep ecology the belief that human life is just one of many equal components of a global ecosystem, ecofeminism asserts that one cannot disentangle anthropocentrism and androcentrism, nor critique the culture/nature dualism without providing a gendered analysis of how this dualism has functioned historically to legitimise the dominations of women and nature.5 By defamiliarising our conventional exchanges with nature, ecofeminism attempts to shift perceptions of other life forms – the more than human – as well as question received ideas about what it means to be human.

In recent decades environmentally conscious artists have embraced nature through humbling gestures of reconciliation, challenging the modernist belief in the dominance of “man” as rational being, along with its correlate, the environmental and social degradations of industrial capital. Ecofeminism informed many of these actions and highlighted the gendered dualistic thinking underpinning Western understandings of nature through inter-species and intersectional ecological actions.6 Ecofeminism has also informed recent scholarship and art practices associated with the “new materialism” that similarly realigns our understandings of life and agency. The ecofeminist imagination operating in such work materially confronts us with the different modalities of objects, setting us up for interactions that heighten our sense of the thingness of the world, including ourselves. As philosopher Jane Bennett suggests, such an approach allows passage to a more complex and more ethical view of what it means to occupy this planet, where human/object, human/environment and material/spirit are understood not as separate, but as integrated.7 With this understanding could come an enhanced political agency that is at home with mystery and uncertainty, and that operates holistically rather than privileging the place of the human subject, and in particular, reason.

Such an integrative conception of the human and more than human world is at the heart of many First Nations’ ways of being. In Australian Aboriginal belief systems, Country embodies the relatedness of land and culture: it is “a place that gives and receives life. Not just imagined or represented, it is lived in and lived with […] Country is a living entity with a yesterday, today, and tomorrow, with a consciousness, and a will toward life.”8 Country is the bedrock of culture, as the Earth is vested with the power and knowledge of ancestorial creator beings. This understanding of the intimate landscape necessarily recognises First Nations ownership and stewardship, an acknowledgment embedded in many First Nations’ artworks that link ecology and art to identity and cultural survival, and assert that loss of identity goes hand in hand with environmental degradation.

Julie Gough (b. 1965) is a Trawlwoolway artist, writer and curator whose practice addresses the historical and ongoing trauma of the First Peoples of Lutruwita (Tasmania), including the experiences of her own family. Working with archives and stories, she makes films and installations that reinterpret particular places whose significance has been covered over or forgotten. In her works Country, as identity and as ecological phenomenon, are inextricable. In the most recent Biennale of Sydney (rīvus, 2022), which centred on the political agency of rivers and wetlands, J. Gough presented p/re-occupied (2022), a video projection with mixed media, including sound, kayak and rocks.9 The video follows the artist as she kayaks along several interconnecting rivers and tributaries in the Midlands of Lutruwita: her journey is a ritual of repatriation, to return facsimiles of cultural belongings, namely ancient stone tools long ago removed to museum collections, to ancestral waterways. At the same time the journey serves to return the First Nations names to these rivers, words “that respect their past and purpose and alliterate their flow since invasion, since colonisation. Survivors. Kin” – paranaple (Mersey River), panatana creek, tinamirakuna (Macquarie River) and lokenermenanya (Clyde River). According to the artist,

To be home, truly, on Country, is to become it. Particles. Substance of place. Belonging. Inhale. Exhale. Everything seems to swirl around, to gather, reform, then set out again […] When I kneel by a river on my island home, I don’t need to see my reflection to be grounded. Our Old People are in the wind, my imprint in that mud is the same repeated, over millennia, by family.10

Leanne Tobin (b. 1961) is a multidisciplinary artist of English, Irish and Aboriginal heritage, descended from the Buruberong and Wumali clans of the Dharug, the ancestral peoples of Greater Sydney. In her practice, which is often community based and collaborative, the desire to nurture Country brings together concerns around recovering stories of the Old People and caring for the more than human world. L. Tobin also featured in rīvus, with Ngalawan – We Live, We Remain: The Call of Ngura (Country) (2021), a sculptural installation, video and participatory weaving work that brought to life the Dharug story of Gurrangatty, the ancestral eel that long ago created the rivers and mountains. The work was spread across two locations to allow visitors to walk part of the path of the eel’s lifecycle; this is a phenomenal journey that sees the eels climb dams and creep over land as they follow their Songline to the Coral Sea, thousands of kilometres north, to spawn, adopting the colours of the river as they move between fresh and saltwater. The sculptural installation comprised of longfineels sinuously crafted in hand-blown glass, made in collaboration with glass artists Ben Edols (b. 1967) and Kathy Elliott (b. 1964), transparent and speckled to evoke the epic adaptive transformations the animals undergo. L. Tobin accompanied these with an animated video and a public workshop that allowed for more extended conversations about this creation story.

The eel’s adaptive transformations and survival in the wake of environmental degradation resulting from overdevelopment and pollution endemic to extractive capitalism, echo those of the Dharug people in the face of ongoing colonial violence. The Dharug are the custodians of Sydney’s Parramatta/Burramatta River, the traditional name translating to “where the eels lie down”. In this work L. Tobin recovers the name to affirm the relation between culture and the more than human:

Today, us Dharug move like eels between two worlds. We have morphed and adapted to new ways imposed on us. First to be colonised and first to lose colour, over time we’ve learned to adapt and become the river. Like eels we have never left. Where once we were hidden, our collective voice now rises to speak the truth.1

V. Plumwood’s idea that the West’s master form of rationality has been unable to acknowledge its dependency on nature, relegating nature to the sphere of “inferior” others and distorting our knowledge of the world in a way that threatens our very survival,12 has been a key source of inspiration for Melbourne/Naarm-based artist Patricia Piccinini (b. 1965). Since the 1990s she has challenged conventional views of the duality of nature and culture through compelling material experiments that manifest in human/technology hybrids. Her sculptural objects question Western philosophical traditions privileging mind over body and the placement of the human subject and cognition at the apex of life on Earth. She imagines a world where such hierarchies no longer rule; a world in which machines and matter get amorous and feel family-bound (The Lovers, 2011; The Pollinator, 2018), where marvellous creatures evolved from the unpredictable interaction of disparate genetic material provide human comfort (Kindred, 2018), and where objects call out to us, reminding us of the limits of our power and the rich possibilities of listening to intelligences other than our own (The Naturalist, 2017). Her work brings to mind J. Bennett’s description of “vital materialists” whose “sense of a strange and incomplete commonality with the outside may induce (us) to treat non-humans – animals, plants, earth, even artefacts and commodities – more carefully, more strategically, more ecologically”.13

P. Piccinini’s exhibition, A Miracle Constantly Repeated (2021-2022) in the magisterial reclaimed ballroom above Flinders Street Station in Melbourne, was centred around the proposition that the distinctions we have made between nature and culture, human and animal, structure and wildness, are failing us and the planet. She observes, “We’ve inherited this idea that we are here and nature’s over there. That distinction? That boundary? It actually doesn’t work anymore.” Through her artwork, P. Piccinini asks:

How do we build our lives together with other, more-than-human animals? And how can it be a nurturing relationship? How can we have an understanding and experience of nature, which is not just about this very traditional idea of pristine nature, untouched by humans? Because that doesn’t exist, and the idea is not workable anymore.14

The practices discussed here evoke the ecofeminist desire to capture the irrepressible productive drive of the world, where organic and inorganic matter interact in complex ways that belie the assertion of human will, where the very notion of “an environment” comes into question, given it assumes a distinction between humans as agents and their context as passive. The work of First Nations artists Julie Gough and Leanne Tobin foreground the significant intersections between ecofeminist rethinking and deep ancestral knowledge of Country. As L. Tobin says,

Rivers teem with life. All living things in and along the river depend on the river. Water is fundamental in Mother Earth’s cycle of growth and regeneration. Rivers distribute that life force. The Old People understood our interconnection and reliance and their lives evolved around ensuring the health and continuation of that life force. We are all interconnected: what affects one affects us all.15

Dr Jacqueline Millner is Professor of Visual Arts at La Trobe University. Her books include Conceptual Beauty: Perspectives on Australian Contemporary Art (Artspace, 2010), Australian Artists in the Contemporary Museum (Ashgate, with Jennifer Barrett, 2014), Fashionable Art (Bloomsbury, with Adam Geczy, 2015), Feminist Perspectives on Art: Contemporary Outtakes (Routledge, co-edited with Catriona Moore, 2018), Contemporary Art and Feminism (Routledge, 2021 with Catriona Moore) and Care Ethics and Art (Routledge, 2022, co-edited with Gretchen Coombs). She has curated major exhibitions and received prestigious research grants from the Australian Research Council, Australia Council and Create NSW.

Interior design for the anonymous men of Reddit

Who’s Looking Out For Young People And Future Generations?

Crispy pea fritters by Nagi

Sub-out the dairy and replace with vegan options…it still will taste amazing!

Here’s how to make it. I love that the only thing you need to pull out the cutting board for is to slice up some green onion!

- Batter first – Put the flour, cornflour, egg, milk, garlic powder, salt and pepper into a bowl and mix to combine.

- Frozen peas – Add the peas, still frozen, plus the cheese and green onion. Then mix so the peas are coated in the batter. It will look like there is not enough batter. Have faith – the little there is sets when cooked and glues the peas together (the cheese helps too). Too much batter = pancake situation = crispiness compromised = disappointing!

- Pack to measure – Scoop up the batter using 3 tablespoon cookie scoop (# 20) or a 1/4 cup measure. Pack it in tightly.

- Flatten – Place / flick the batter into the pan.

- Flatten the mound to about 1.25cm / 0.5″ thick.

- Flattened! Then repeat with remaining batter to make 4 or 5 at a time.

- Cook for about 1 1/2 minutes on each side until it is deep golden and crispy. Adjust the heat as needed if it’s browning too quickly or slowly. And be brave – make sure you cook until very golden, because golden = crispy!💡TIP: Don’t skimp on oil for fritters. Heat enough oil into your pan so the base is covered completely. Remember, oil thins out as it heats up so it will spread more. If you don’t use enough oil, your fritters will end up burnt rather than golden and crispy which is so disappointing.

- Drain the excess oil on paper towels then repeat with remaining batter. You should get 9 or 10, depending on how tightly you pack the cup. Then serve with the Lemon Yogurt Dipping Sauce! (Which is just a mix together situation so I skipped the step photos for that.)

Harnessing the warm and nourishing resource of self-energy by Dan Roberts

Dan Roberts writer and psychotherapist creates these regular, incredibly helpful, supportive and caring emails. I loved them so much I had to share this one, you will not regret subscribing to him. Find them all on his website.

As regular readers will know, I am a big fan of internal family systems (IFS) therapy, having taken a deep dive into this warm, compassionate, transformative model. There is something about IFS that resonates deeply with me and my clients, who seem to love it too. It’s also hugely popular globally –in fact, to train in IFS you have to enter a lottery, as trainings are so oversubscribed – so it clearly resonates with millions of people around the world too.

If you have encountered IFS in these posts or elsewhere, you will know that the idea of Self is key – this is the inner resource we all possess, famously described by Dr Richard Schwartz, founder of IFS, as having eight qualities (that all happen to begin with C – Dr Schwartz is a big fan of alliteration): Calm, Compassion, Clarity, Confidence, Curiosity, Courage, Connectedness and Creativity.

The expression of these qualities, both inside your mind and body and with other people, is called Self-energy. This may sound a little mysterious, or even New Age-y, but there are many brain-based ways of understanding it. One idea I often share with my clients is that the body has innate healing processes, which is easy to understand if you imagine breaking your wrist in a skiing accident. It would hurt, of course, but hopefully you would find a nice, friendly doctor in your ski resort who would X-ray your arm, find the break and then protect it with a plaster cast.

Gary’s Gang – Let’s Lovedance Tonight

Snake Eater (1072)

Snake eater. Beatus of Liébana, Commentaria in Apocalypsin (the ‘Beatus of Saint-Sever’), Saint-Sever before 1072. BnF, Latin 8878, fol. 13r.

#medieval #MedievalArt via Medieval Illumination

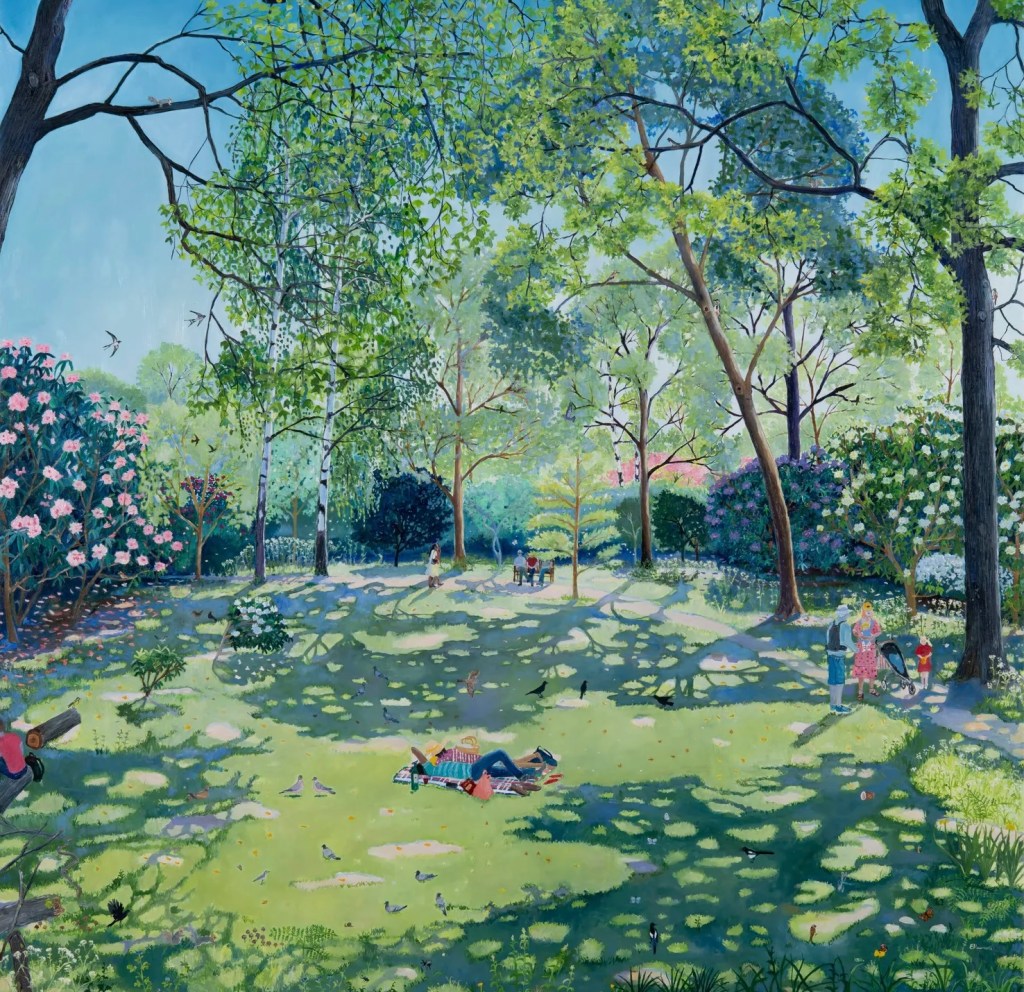

Dreaming in Summer by Emma Haworth (2025)

Emma Haworth’s practice is built upon meticulous observation of the ebb and flow of modern metropolitan life: in the streets, the parks, the squares of London, New York, Paris, or some other great urban center. Haworth distills both telling, individual detail—the plastic bag caught in the branches of a winter tree, the Hyde Park sunbather’s slim-line briefcase—and a vital sense of the whole panorama—the quality of light falling through London plane trees or bouncing off New York skyscrapers, the sense of movement in a crowd, the sense of pleasure on a bank holiday. Haworth was awarded the Woodhay Picture Gallery Prize by the New English Art Club in 2001, and was nominated for the Hunting Art Prize at the Royal College of Art in both 1999 and 2000. In 2010, she won joint First Prize in the National Art Open Competition, as well as First Prize in the Sunday Times Watercolour Competition. On Sale via Artsy

Did you enjoy this collection? let me know what you think of it below. Thank you for reading my dear friends!

One thought on “10 Interesting Things I Found on the Internet #171”