An inward-facing, biophilic and enchanting home in Singapore

Travelling in the wake of the Vikings

Greer Jarrett, a doctoral student at Lund University spent the past three years sailing a replica Viking faering boat over 5,000 kilometers along ancient Norse maritime routes.

His research involved constructing a traditional Viking-era sailing vessel and navigating it through challenging conditions, including storms, snow and hale on open waters. He and his team identified four potential Viking harbors along the Norwegian coast. These findings suggest a decentralized network of resting places on smaller islands where Vikings met and interacted. The video provides a fascinating insight into a seaborne and maritime view that the Vikings once may have had.

Living in the age of ‘Hypernormalisation’

Hypernormalization” is a heady, $10 word, but it captures the weird, dire atmosphere of the US in 2025.

First articulated in 2005 by scholar Alexei Yurchak to describe the civilian experience in Soviet Russia, hypernormalization describes life in a society where two main things are happening.

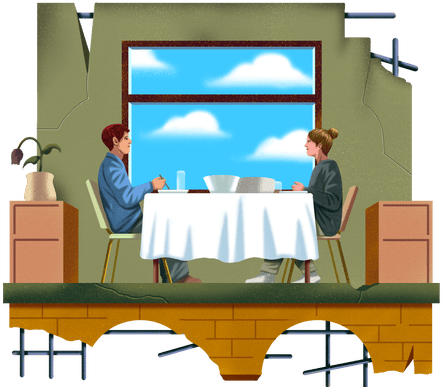

The first is people seeing that governing systems and institutions are broken. And the second is that, for reasons including a lack of effective leadership and an inability to imagine how to disrupt the status quo, people carry on with their lives as normal despite systemic dysfunction – give or take a heavy load of fear, dread, denial and dissociation.

“What you are feeling is the disconnect between seeing that systems are failing, that things aren’t working … and yet the institutions and the people in power just are, like, ignoring it and pretending everything is going to go on the way that it has,” Harfoush says in her video.

Within 48 hours, Harfoush’s video accrued millions of views. (It currently has slightly fewer than 9m.) It spread in “mom groups, friend chat circles, political subreddits, coupon communities, and even dog-walking groups”, Harfoush tells me, along with variations of: “Oh, so that’s what I’ve been feeling!” and “people tagging their friends with notes like: ‘We were just talking about this!’”

Why hypernormalization is relevant in the US

The increasing instability of the US’s democratic norms has prompted these references to hypernormalization.

Donald Trump is dismantling government checks and balances in an apparent advance toward a “unitary executive” doctrine that would grant him near-unlimited authority, driving the US toward autocracy. Billionaire tech moguls like Elon Musk are helping the government consolidate power and aggressively reduce the federal workforce. Institutions like the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration, which help keep Americans healthy and informed, are being haphazardly diminished.

Globally, once-in-a-lifetime climate disasters, war and the lingering trauma of Covid continue to unfold, while an explosion of generative AI threatens to destabilize how people think, make a living and relate to each other.

It’s reading an article about hunger and genocide, only to scroll down to a quiz about: ‘What Pop-Tart are you?

Rahaf Harfoush, digital anthropologist

For many in the US, Trump 2.0 is having a devastating effect on daily life. For others, the routines of life continue, albeit threaded with mind-altering horrors: scrolling past an AI-generated cartoon of Ice officers arresting immigrants before dinner, or hearing about starving Palestinian families while on a school run.

Hypernormalization captures this juxtaposition of the dysfunctional and mundane.

It’s “the visceral sense of waking up in an alternate timeline with a deep, bodily knowing that something isn’t right – but having no clear idea how to fix it”, Harfoush tells me. “It’s reading an article about childhood hunger and genocide, only to scroll down to a carefree listicle highlighting the best-dressed celebrities or a whimsical quiz about: ‘What Pop-Tart are you?’”

In his 2016 documentary HyperNormalisation, the British film-maker Adam Curtis argued that Yurchak’s critique of late-Soviet life applies neatly to the west’s decades-long slide into authoritarianism, something more Americans are now confronting head-on.

“Donald Trump is not something new,” Curtis tells me, calling him “the final pantomime product” of the US government, where the powerful are abandoning any pretense of common, inclusive ideals and instead using their positions to settle scores, reward loyalty and hollow out institutions for personal or political gains.https://interactive.guim.co.uk/uploader/embed/2023/10/archive-zip/giv-13425WMrLo2pc9VIk/?dark=false

Trump’s US is “just like Yeltsin in Russia in the 1990s – promising a new kind of democracy, but in reality allowing the oligarchs to loot and distort the society”, says Curtis.

Why the concept of hypernormalisation is useful

Witnessing large-scale systems slowly unravel in real time can be profoundly surreal and frightening. The hypernormalization framework offers a way to understand what we’re feeling and why.

Harfoush created her video “to reassure others that they’re not alone” and that “they aren’t misinterpreting the situation or imagining things”. Understanding hypernormalization “made me feel less isolated”, she says. “It’s difficult to act when you’re uncertain if you’re perceiving reality clearly, but once you know the truth, you can channel that clarity into meaningful action and, ideally, drive positive change.”

Naming an experience can be a form of psychological relief. “The worst thing in the world is to feel that you’re the only one who feels this way and that you are going quietly mad and everyone else is in denial,” says Caroline Hickman, a psychotherapist and instructor at the University of Bath specializing in climate anxiety. “That terrifies people. It traumatizes people.”

People who feel the “wrongness” of current conditions acutely may be experiencing some depression and anxiety, but those feelings can be quite rational – not a symptom of poor mental health, alarmism or a lack of proper perspective, Hickman says.

“What we’re really scared of is that the people in power have not got our back and they don’t give a shit about whether we survive or not,” she says.

Marielle Greguski, 32, a New York City-based retail worker and content creator, posted about everyday life feeling “inconsequential” in the face of political crisis. Greguski says the outcome of the 2024 election reminded her that she lives in a “bubble” of progressive values, and that “there’s the other half of people that are not feeling the same energy and frustration and fear”.

To Greguski, the US’s failings are not only partisan but moral – like the racism and bigotry that Trump’s second term has brought out of the shadows and into policy.

Greguski is currently planning a wedding. It’s hard to compartmentalize “constant cruelty, things that don’t make sense”, she says. “Sometimes I’ll be like: ‘I have to put aside X amount of money for the wedding next year,’ and then I’m like: ‘Will this country exist as we know it next year?’ It really is crazy.”

The effects of hypernormalisation

Confronting systemic collapse can be so disorienting, overwhelming and even humiliating, that many tune it out or find themselves in a state of freeze.

Greguski likens this feeling to sleep paralysis: “basically a waking nightmare where you’re like: ‘I’m here, I’m aware, but I’m so scared and I can’t move.’”

In his 1955 book They Thought They Were Free: The Germans, 1933–45, journalist Milton Mayer described a similar state of freeze in German citizens during the rise of the Nazi party: “You don’t want to act, or even talk, alone; you don’t want to ‘go out of your way to make trouble.’ Why not? – Well, you are not in the habit of doing it. And it is not just fear, fear of standing alone, that restrains you; it is also genuine uncertainty.”

“People don’t shut down because they don’t feel anything,” says Hickman. “They shut down because they feel too much.” Understanding this overwhelm is an important first step in resisting inaction – it helps us see fear as a trap.

Curtis points out that governments may intentionally keep their citizens in a vulnerable state of dread and confusion as “a brilliant way of managing a highly febrile and anxious society”, he says.

When we feel powerless in the face of bigger problems, we “turn to the only thing that we do have the power over, to try and change for the better”, says Curtis – meaning, typically, ourselves. Anxiety and fear can trap us, leading us to spend more time trying to feel better in small, personal ways, like entertainment and self-care, and less time on activism and community engagement.

How to overcome hypernormalisation

Progressive commentators have urgently called for moral clarity and mobilization in response to changes like the cuts to USAID funding, which has resulted in an estimated 103 deaths per hour across the globe; the dismantling of the CDC; and Robert F Kennedy’s campaign against vaccine science.

“Where is the outrage?” asks the Nation’s Gregg Gonsalves. “Too many lives are at stake to rest in this bizarre moment of frozen agitation.”

“I don’t know if there’s a massive shift toward racism as much as an expanded indifference toward it,” the historian Robin DG Kelley said in a February interview with New York Magazine. “People are just kind of like: ‘Well, what can we do?’”

Experts say action can break the spell. “Being active politically, in whatever way, I think helps reduce apocalyptic gloom,” says Betsy Hartmann, an activist, scholar and author of The America Syndrome, which explores the importance of resisting apocalyptic thinking.

Greguski and a co-worker have been helping distribute multilingual information about legal rights and helpline numbers, to be used in the event of Ice raids.

“It’s easy to feel like: ‘Oh, I’m in community because I’m on TikTok,’” she says. But genuine community is about “getting outside and talking to your neighbor and knowing that there’s someone out there that can help you if something really bad goes down,” she says.

Being active politically, in whatever way, I think helps reduce apocalyptic gloom

Betsy Hartmann, author of The America Syndrome

“You’re actually out there talking to people, working with people and realizing there are so many good people in the world, too, and maybe feeling less isolated than before,” says Hartmann.

“But I also think we need a broader vision,” Hartmann notes. She suggests looking to resistance efforts against authoritarianism in countries like Turkey, Hungary and India. “How might we be in international solidarity? What lessons can we learn in terms of rebuilding sophisticated, complex government infrastructure that’s been hacked away at by people like Elon Musk and his minions in a more socially just and sustainable way?”

“We are in a period now when it’s absolutely essential to protest,” says Hartmann, citing the Harvard professor Erica Chenoweth, who argues that just 3.5% of a population engaging in peaceful protest can hold back authoritarian movements.

Is ‘chic’ political? In Trump 2.0, the word stands for conservative femininityRead more

What makes dysfunction so dangerous is that we might simply learn to live with it. But understanding hypernormalization gives us language – and permission – to recognize when systems are failing, and clarifies the risk of not taking action when we can.

In 2014, Ursula Le Guin accepted the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, saying: “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

Harfoush reflects on this quote often. It underscores the fact that “this world we’ve created is ultimately a choice”, she says. “It doesn’t have to be like this.”

We have the research, technologies and wisdom to create better, more sustainable systems.

“But meaningful change requires collective awakening and decisive action,” says Harfoush. “And we need to start now.”

Faktor X – Aura Sniffers

Serpents of Libya (1460)

Serpents of Libya. Faits des Romains, Paris ca. 1460-1465. BnF, Français 64, fol. 391v.

#medieval #MedievalArt via Medieval Manuscripts

Adam Keeling of Whichford Pottery

How I learned to stop worrying and love the snakes in my ceiling

By Christine, via the Guardian.

Overcoming my terror of new housemates was gradual but by observing them I learned that pythons can be beautiful and clever

Fifteen years ago, while perched on the back deck of my 1920s tin and timber Queenslander home in Brisbane, I realised I was being watched.

I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end and I spun around to discover a snake dangling from the lattice. Terrified, I rushed inside and locked the door. Clearly, fear is not rational, or I would have understood that serpents don’t have arms.

I adore lizards. I’ve visited Indonesia’s komodo dragons and cuddled shinglebacks in Australia’s red centre but I have always been more scared than seduced by snakes.

When I was growing up in country Queensland in the 1970s, we often encountered venomous snakes – our tiny town even had a Black Snake Creek. Running around our back yard it was common to almost trip over a deadly king brown. Parental advice: “Just freeze. Keep an eye on it. And sing out to Mum.”

Mum would shout to Dad, who was a bit of a Steve Irwin-type, and he’d grab a hessian bag, casually toss the reptile in, then escort it up to the farm shed to eat the rats.

Before living in Brisbane, I’d never encountered a python, only venomous snakes. My anxious mother understandably did a hard sell on the horrors of snake bites, lest one of her four children succumb to their fangs. This gave me the same kind of fear you’d get playing hide and seek as a kid. You love the game but there’s an element of adrenaline when found. Should I fight or flee?

Fast forward several decades and I’m living 4km from Brisbane’s city centre, with a bushy back yard which I have deliberately grown wild to encourage possums, kookaburras, water dragons and sulphur-crested cockatoos. And, it turned out, 10 years into living on the property, non-venomous eastern carpet pythons.

Overcoming my terror of these new housemates was gradual. Critics say it’s wrong to anthropomorphise an animal but watching the serene Sylvia slither from my ceiling into the cypress pine which overhangs my back deck was the first step. By naming her – I assumed it was a she from her gentle energy – and observing her I quickly learned what a beautiful and clever creature she was.

I loved how she would dislocate her jaw to yawn or when hungry. How she used her forked tongue to smell. I was fascinated when her eyes would go milky in the days before she shed her skin, a gift she would leave hanging over the deck like stockings. On hot days she would stretch her ever increasing girth along the back deck and allow me to run my hands along the curves of her spine.

Sylvia eventually grew too curvy to squeeze back into the ceiling cavity. Carpet pythons are territorial and, soon after, another arrived, then another.

Straight after Sylvia came Son of Satan, or Shitty for short. Sadly Shitty thought he was a taipan, one of the few Australian snakes which are actually aggressive, had remarkable eyesight and hearing, and would strike at my back-door glass whenever he glimpsed me inside the house.

For a brief moment my fear returned and the back deck became off limits, until I reminded myself that snakes, like humans, all have different personalities. And that this was still a wild animal. From Shitty, I learned respect.

There are snake catchers galore in south-east Queensland but many of us choose to live with our carpet pythons – even the grumpy ones. They are great for the environment as they eat bush rats, and keep noisier neighbours like possums from moving into roofs.

Shitty has now moved on and I’m left with Slinky, a scrawny juvenile who is, at this stage, a hopeless hunter. This will change and eventually Slinky will leave my ceiling too. While I’m not sure who’s lurking to move in next, I’m learning more about these incredible, quiet creatures (you should see them climb) and I look forward to the day another sanguine serpent like my beloved Sylvia graces my back deck.

The Making of Ultraman by Japanese Telecom

How to make fried tofu with chilli crisp – recipe

Prep 15 min

Cook 15 min

Serves 2

About 280g firm or extra-firm tofu – if using silken, skip step 3

Salt and black pepper

4 tbsp cornflour, or other starch (optional)

Neutral oil, for deep-frying

For the chilli crisp (if making)

1½ tbsp Sichuan peppercorns

3-4 tbsp gochuharu, or other chilli flakes to taste

30g roasted salted peanuts, or soybeans, roughly chopped

1 tbsp fermented black beans, finely chopped (optional)

250ml neutral oil

1 long shallot, or 2 round ones, peeled and thinly sliced

6 garlic cloves, peeled and thinly sliced

1 tsp sugar (optional)

¼ tsp MSG powder (optional)

1 A note on the tofu

Firm or extra-firm tofu is the best choice for frying – silken will be creamy inside, and pressed tofu chewier and more meaty. For the neatest results, cut into bite-sized nuggets about 3cm x 2cm. If you value crunch over appearance, break it into bite-sized pieces instead; the rougher edges will crisp up better than perfectly flat surfaces.

2 Soak the tofu

For maximum crispness, remove as much excess moisture from the tofu as possible before cooking it. Fill a bowl or pan with boiling water and season very generously with salt, so it tastes like the sea. Drop in the tofu, leave to soak for 15 minutes (the hot water will draw out liquid from the centre of the tofu; the salt’s just for seasoning).

3 Dry the tofu

Meanwhile, line a baking tray with kitchen paper or a clean tea towel. Drain the tofu, put it on the tray and top with more paper or another towel. Put another baking tray or chopping board on top, weigh that down with a couple of tins, or something else heavy, and leave to sit for 15 minutes.

4 To coat, or not to coat?

Coating the tofu is optional, but it will help with crunchiness. Put the cornflour or other starch (eg, plain or rice flour, potato starch, etc) in a shallow bowl and season generously with salt and pepper, or other spices of your choice. Add the pieces of tofu, toss to coat lightly, then shake off any excess.

5 Fry the tofu

Meanwhile, fill a deep pan by about a third with a neutral oil and heat to 180C (or until bubbles form around the end of a wooden chopstick). Add the tofu, in batches, if need be, stir once, then fry until crisp and golden. Drain on kitchen paper, season and serve with a dipping sauce, or toss through a stir-fry.

6 And now for some homemade chilli crisp

You may wish to serve your fried tofu (and just about everything else you eat, for that matter, from eggs to rice to steamed veg) with chilli crisp. Though there are many delicious ready-made versions out there, making your own allows you to tweak the basic formula (oil, chilli, crunchy beans or nuts) to suit your own taste.

7 Toast and grind the spices

Toast the peppercorns and/or any other whole spices (eg, black peppercorns, cumin and/or coriander seeds, star anise, cinnamon) in a dry pan, then roughly crush. Chilli-wise, I prefer medium-hot flakes such as Korean gochugaru, but experiment with different varieties. Toast briefly, then grind, if necessary. Put the peanuts, black beans and all the spices in a large heatproof bowl.

8 Flavour the oil

Set a heatproof sieve over a heatproof bowl. Pour the oil into a wide frying pan, add the sliced shallot and put the pan on a medium heat. Fry, stirring, until the shallot is crisp and golden, then drain into the sieve and return the oil to the pan. Add the garlic, cook until pale golden, then drain again.

9 Mix and jar

Pour the hot oil on to the spice and nut mixture, then stir in the sugar and MSG, if using; you may also wish to add salt, depending on how salty your peanuts and black beans are. Leave to cool completely, then stir in the fried shallots and garlic. Decant into a clean jar, seal and store in the fridge.

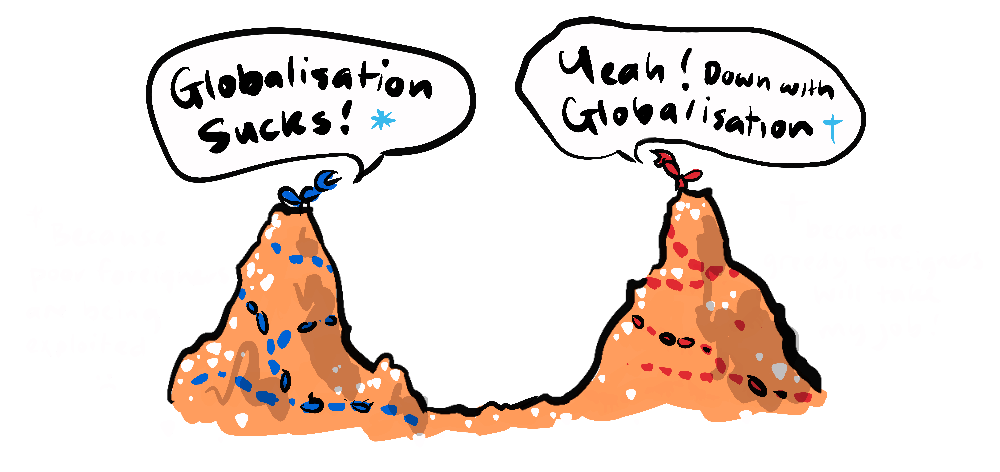

How contagious beliefs spread by Non-Zero Sum Games

The incredible blog Non-Zero Sum Games has some incredible interactive posts about philosophy, ideology, psychology, politics, and loads more. I am in love with this website and how it easily unpacks complex topics.

Humans are social animals, and as such we are influenced by the beliefs of those around us. This simulation explores how beliefs can spread through a population, and how indirect relationships between beliefs can lead to unexpected correlations.

Strange bed-fellows

There are some strange ideological bed-fellows that emerge in the realm of human beliefs. Social scientists grapple with the strong correlation between Christianity and gun ownership when the “Prince of Peace” lived in a world without guns. Similarly there are other correlations between atheism and globalisation or pro-regulation leftists who are also pro-choice, and then we have the anti-vax movement infiltrating both the far-left and far-right of politics. Read more

Xenobia Bailey

Xenobia Bailey, US fine artist, designer and fibre artist known for her large scale crochet pieces and hats #WomensArt

Did you enjoy this collection? let me know what you think of it below. Thank you for reading my dear friends!

Hypernormalization – how fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading Wynn I’m so glad this resonated with you 💗

LikeLike

Snakes and hypernormalisation ….both excellent reads!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad you liked these Kev…hope you are going well 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

https://youtu.be/Gr7T07WfIhM?si=Jh0-Bc0-htnsD4Fs

this doco is Brillant. G

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regarding “hypernormalization”, my brother (a behavioral psychologist who went into Law) once quipped that the human tendency is to respond to crisis. Watching a mountain lion stalk a herd of deer, this came to mind. The spooked animals moved aggressively away… but only just far enough to be out of sight. And then they went back to obliviously grazing. Natural selection rewards efficiency, and that means doing just enough to keep from dying… and nothing more. It’s hardwired into our brains to respond only when in immediate danger.

And so, we live in a world of hyperbole. Anyone who has anything to sell, whether a product or a service, or a dream or a reality, or an opportunity or a scam, or a plan or an ideology, it has to be sold as a crisis – or at the very least as the solution to one. And constantly bombarded with these kinds of messages to the point of no longer being able to distinguish the mountain lion from the rustling of the grass, we go back to grazing.

LikeLiked by 2 people