The Colour of the Sky After Rain

Chinese ancient artistry 🎨

Stella by Jam & Spoon (Barracuda mix by Moby)

Wholesome Meme: Be Nice To Yourself Frog

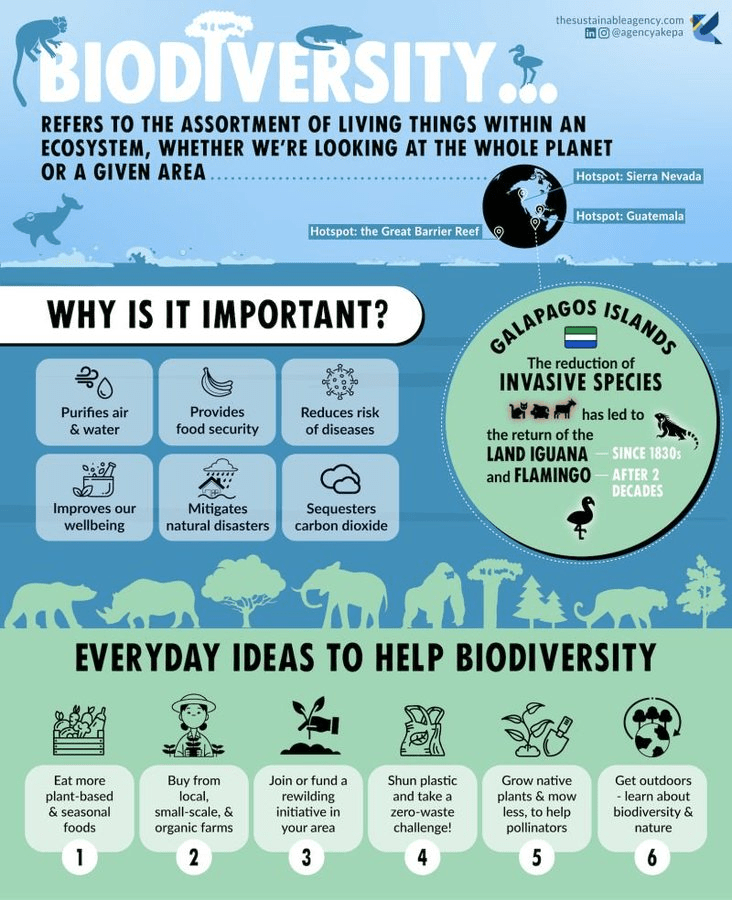

Biodiveristy: Why is it important?

Young couple score a gig as caretakers of a remote Irish island

Camille Rosenfeld and James Hayes have scored a dream gig: six months as caretakers of Ireland’s uninhabited Great Blasket Island. With no electricity or Wi-Fi, the rugged island off County Kerry promises a simpler life surrounded by seals, dolphins, wildflowers and ancient Gaelic ruins. Chosen from thousands of applicants, the young couple will oversee a small café and five holiday cottages, soaking in windswept solitude and starry skies. For Rosenfeld, it’s the joy of disconnection; for artist Hayes, a wellspring of creative inspiration. As they say—it’s less a job, more a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Read more

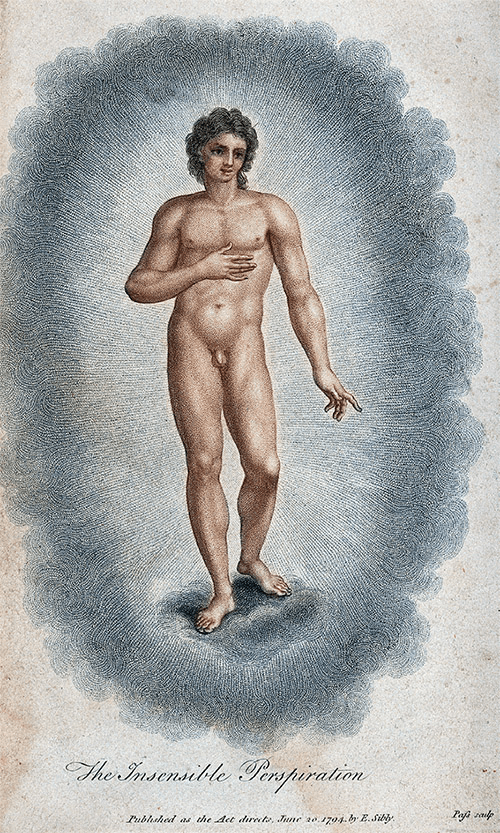

The Long History of the Human Aura

From religious iconography to modern mysticism, the human aura has been a subject of fascination across centuries and cultures. Via MIT Press Reader

By: Jeremy Stolow

Although few of us have ever seen an aura with our own eyes, we all seem to know more or less what it is supposed to look like: a faintly luminescent cloud or haze, a ring of flames, a solar disk, a crown of lightning. These are some of the many ways that artists, healers, clairvoyants, and occult seers at different times and places have visualized physical bodies or body parts as encased within some sort of radiant energy or force.

While not always traveling under the same name, the aura figure has in fact enjoyed a remarkable historical and cross-cultural reach. It has long been available as an artistic device used to mark the presence of deities, saints, emperors, and other specially endowed persons. It has taken shape in anatomical illustrations and diagrams representing the vital forces that are said to constitute our “subtle” physiology. And it has materialized in patterns of light registered on photographs, which are understood to reveal the contours of mysterious energy fields lying hidden in the very fabric of the universe. Folded into its diverse artistic, religious, scientific, therapeutic, and commercial enterprises, the aura figure seems as old as it is ubiquitous. One of its best-known commentators, Walter Benjamin, went so far as to suggest that auras “appear in all things.”

Folded into its diverse artistic, religious, scientific, therapeutic, and commercial enterprises, the aura figure seems as old as it is ubiquitous.

Of course, Benjamin was speaking allegorically, not offering a literal description of the aura. Yet as it happens, our very ability to draw a line between literal and allegorical talk about auras rests on a decisive turn that only occurred in the more recent history of the aura’s long career.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, an unprecedented effort was undertaken to investigate the credibility and plausibility of the aura, alongside other phenomena that confounded available naturalist explanations. The outcome of such efforts, roughly stated, was the consolidation of a monopoly opinion among scientific authorities that auras do not really exist in the natural world. Henceforth, their existence could only take the form of cultural constructions, figments of the imagination, pseudoscientific distortions, or technologically induced special effects.

And yet, despite the considerable force of this consensus, efforts to picture auras have only grown, not abated. As I document in some detail in “Picturing Aura,” successive generations of actors have in fact been busy at work adopting and adapting evolving instruments, techniques, platforms, institutions, and markets in their ongoing efforts to capture the aura, penetrate its mysteries, and extend its visible presence.

Some readers will rightly want to know, first of all: What exactly is an aura? Let me begin with an illustration. The image above was originally published as the frontispiece to “The Human Aura: A Study,” a late 19th-century treatise penned by Auguste Jean Baptiste Marques, a medical doctor, diplomat, and erstwhile General Secretary of the Aloha (Hawaii) Branch of the Theosophical Society. Here we see the silhouette of an upper torso and head of what is presumably an “ordinary” human body. Around it is placed a series of colored, cloudlike arches, each of which appears to be wider and more translucent than the previous one. According to the text along the bottom of the panel, these arched layers cincturing the silhouetted body figure are assigned names derived from various Buddhist and Hindu Tantric idioms, such as the “kamic sheath,” while the outermost layer, encompassing all the others, is named the “auric egg.”

The author warns the reader that the width of these layers is not proportionally precise; their relative scale has been adjusted in order to fit onto the page. When taken diagrammatically, however, this illustration establishes the contours of a life-form that does not exactly begin or end where we might normally suppose — at the surface of the skin — but rather somehow extends beyond it. This gradually dissipating, ever-more translucent terrain “beyond” the physical body demarcates the realm of the aura.

Theosophists like Marques played a key role in the consolidation of a particular way of conceiving of the aura as a “subtle, invisible essence or fluid that emanates from human and animal bodies and even things,” which has dominated our understanding of this phenomenon down to the present day. Nevertheless, neither the word aura nor this double figure of a body and its radiant extension are Theosophical inventions. Both can be discovered, time and again, within what turn out to be very long lines of transmission through which devotees, healers, clairvoyants, synesthetes, and other gifted seers across history have reported their perceptions of auras and have attempted to describe what they saw.

Long before Theosophists or any other modern writers turned to the topic, these testimonials were recorded, reproduced, pictorialized, and interpreted within long-standing traditions of art, science, medicine, and cosmology that lent stability to the aura figure in its many local settings as well as in its far-reaching traffic. It is therefore not coincidental that the image presents us not only with an illustration of “the aura” but also a series of descriptive terms, emphasizing the impossibility of separating perceptual experiences from the discursive as well as figural frameworks in which they are entangled. Visualizing an aura implies that one is first able to recognize its shape and apply its name.

But why aura, of all names? Some clues are offered by the history of the word itself, which derives from the ancient Greek αὔρα, the term for a gentle breeze, an aroma, a breath, or an exhalation or emanation of some sort. According to Greek mythology, Aura was a fleet-winged nymph, one of the daughters of Boreas, the god of the north wind. Swift yet gentle in her movements, Aura personified the very notion of a subtle apparition. It is not surprising, therefore, that her name could eventually be applied to such things as the aroma of a perfume, the arrival of a humor descending on a living body, or the mysterious circles of light surrounding angels, gods, emperors, and other extraordinary beings.

One prominent use of the word can be found in Western medical discourse, beginning with the second-century CE Greek physician Galen’s description of the onset of epileptic fits that sweep over the body, a reference that is preserved in the contemporary medical term, aura epileptica. In all these cases, the tropes of gentle breezes, aromas, and hazy yet luminous emanations invoke things that somehow stand between the grossly physical and the incorporeally spiritual: a rarefied dimension of reality or a tertium quid that defies the strict Platonic-Cartesian distinctions of body and mind, matter and force, or substance and idea.

The second-century CE Greek physician Galen used “aura” to describe the onset of epileptic fits — a meaning still preserved in aura epileptica today.

When applied to the living body, as Marques does in his own illustration, the word aura seems to designate a nearly imperceptible boundary that extends beyond while also hovering around the physical body. In “The Book of Skin,” Steven Connor offers a more recent definition of the aura as an ethereal exoskeleton: a second skin that, like a shadow, is “conceived not as a separate entity that is capable of existence apart from the body.” At once liminal and permeable, forever forming and re-forming itself, this gentle breeze entangles bodily interiors and exteriors within a unity that cannot be dissected or divided any more than one can cut air with a knife.

The rarefied qualities conjured by the word aura have often invited comparison with other figures and terms that likewise seem to break down the barriers of inner and outer, or of material and immaterial. Sometimes invoked through metaphors of vapor or wind, at other times couched in the language of glowing lights, clouds, diaphanous tissues, or refined particulates (such as stardust), this subtle presence has been assigned many names, among them: pranamayakośa, sūkṣma śarīra, qi, ochêma-pneuma, archeus, lumière astrale, perianto, force vitale, psychotronic vibrations, and bioplasma. In their aggregate, they throw into relief a long-standing preoccupation shared among diverse metaphysical traditions, sciences, and knowledge systems, from Neoplatonism to Tantric Buddhism, from Romantic Naturphilosophie to traditional Chinese medicine.

No less influential a figure than Aristotle attempted to address the problem of body/soul (or body/mind) dualism by proposing the existence of a mediator, the phantasmic pneuma: a thin casing surrounding the soul, composed of the same refined substance as the stars, which the philosopher understood to enable that soul to come into contact with the sensory, material world. Working in this Aristotelian framework, medieval Christian theologians such as Thomas Aquinas expounded at length on all manner of things that seemed possible only by virtue of a subtle intermediation between the physical and the spiritual: from the vitalizing warmth of human breath to expressions of friendship and mutual affection, to the agitation of the emotions provoked by the sight of stunning beauty.

For their part, the Renaissance Hermetic “natural magicians” — Marsilio Ficino, Paracelsus, Giordano Bruno, among others — turned to Neoplatonist philosophy for a language that could account for some such pneumatic, subtly mediating figure, which in their understanding linked physical bodies to a vast cosmic network of invisible forces of attraction and repulsion emanating from the planets and the stars. Comparable accounts of an intermediary range of gradations between matter and spirit, body and soul, or between the terrestrial and the celestial, can also be found in numerous non-Western textual, ritual, and medical traditions, including, for instance, the Hindu doctrine of the “third body” (the sūkṣma śarīra), first mentioned in the Upanishads and later taken up as a key theme in Sāṃkhya and Vedānta philosophy and in the practices of yoga and Tantra.

While each of these accounts of auras and aura-like phenomena can be located in its distinct historical and cultural context, it is hard to resist the temptation to collate them into a more general picture. In recent years, a number of scholars have adopted a cross-cultural comparative framework with the precise intention of establishing continuities among practices, concepts, and objects — including the aura — under the rubrics of “subtle matter” and “the subtle body.” Within this framework, the word subtle designates a family of (at least partially) overlapping orientations and perceptions, experiences, techniques, vocabularies, imaginal resources, and knowledge claims elaborated in diverse historical and cultural contexts. However, this search for a general category, even when adopted strictly as a methodological heuristic, partakes in a much longer and more vexed history.

For more than a century, perceived commonalities among diverse Western and Eastern metaphysical traditions have nourished a vibrant tradition of scholarship on comparative religion, just as they have inspired popular writers to fill the “esoterica” section of retail bookstores and, in more recent times, New Age websites, with all manner of wisdom on the cosmic harmonies that are said to bridge the world’s religions, spiritual practices, and enlightened sciences. The classificatory schemes that many present-day scholars, as well as popular writers, rely upon in their general descriptions of such things as “the subtle body” or “the aura” are in fact patterned directly on the prior work of occultist and esoteric writers — Theosophists foremost among them — from over a century ago.

While as a word, a visual figure, and an idea, the aura seems to have enjoyed a remarkably long history, something distinctive was taking shape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One measure of the scale of this shift can be gleaned from the sudden increase in the use of the word in published works in English, French, German, Spanish, and Russian around that time.

According to Google’s Ngram Viewer (a digital tool that charts the frequency of vocabulary appearing in sources printed since 1500), the word aura experienced a dramatic spike between roughly 1890 and 1920 within all these languages. In some cases, such as German and Russian, the word seems to have been almost nonexistent in publications until around 1850, after which its steady growth crests in a veritable explosion of occurrences from the 1890s onward. Here then, roughly speaking, we can mark the birthplace of the modern word aura. One of the most distinctive features of this new usage is a dramatically expanded semantic range: a democratization, so to speak, of a phenomenon formerly reserved for extraordinary bodies and bodily states. In its modern usage, the word aura has been extended across all of creation; to recall once again Marques’s definition cited above, it now references a “subtle, invisible essence or fluid that emanates from human and animal bodies and even things.”

The previous fin de siècle constituted such a decisive moment for this reformulation of the word aura in large part because Theosophists and their fellow travelers were able to take advantage of an unprecedented restructuring of science, technology, religion, and culture during this period. Among them, Theosophist and scholar of esoteric traditions George Robert Stow Mead saw modern science as a tool for uncovering hidden truths about the subtle body. His meditations on the “hitherto undreamed-of possibilities locked up within the bosom of nature” highlight what is in fact a commonplace understanding of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a moment of dizzyingly rapid and profoundly unsettling scientific and technological change, in which established assumptions about matter, energy, and life were openly challenged, to the great interest of journalists, artists, and many other observers.

As registered in diverse arenas of laboratory experiments, popular science magazines and public demonstrations, stage magic and early cinema, trick photography, Spiritualist séances, and new avant-garde art movements, among many other places, the new sciences generated distinctly new ways of making invisible things present and addressing mysterious, hidden dimensions of the cosmos. In this context, esoteric writers such as Marques and Mead were uniquely positioned to redefine the aura and related phenomena as an object of ancient wisdom and also, at the very same time, as a frontier science research topic.

Over the course of the 20th century and up to the present day, these conjunctions of science and occultism provided the framework within which the modern figure of the aura has been defined, visualized, and worked upon. Conceptually, discursively, and even performatively, the purveyors, practitioners, clients, and engaged audiences of the present-day New Age spiritual marketplace rest on the shoulders of their Theosophical forebears such as Marques and Mead. This is not to deny that the instruments, techniques, experts, and visual materials gathered under the rubric of “picturing aura” have sometimes moved onto terrains far removed from the New Age milieu, strictly speaking.

Nevertheless, no account of the practice can be written without taking into account how this earlier history of entanglement of science and occultism shaped the widely distributed sensibilities, modes of reasoning, and techniques of body care for which the visualization of the aura became so indispensable. From the late 19th century to the present day, this confluence of esoteric vocabularies and concepts, new means of technical picture-making, and protocols of scientific observation set the stage upon which the modern history of picturing aura has unfolded.

Jeremy Stolow is Professor of Communication Studies at Concordia University, Montréal, Canada. Among his publications are the books “Orthodox by Design” (University of California Press) and “Deus in Machina” (Fordham University Press). This article is adapted from his book “Picturing Aura: A Visual Biography.”

Dancing is an artform!

Little did the mascot know, approaching that guard would make historyhttps://embed.reddit.com/widgets.js

byu/Cool-Fig-9254 ininterestingasfuck

Funky Grooves and Making a Japanese Curry

This combo just works – cool obscure and funky beats to put you into a good mood along with making a delicious vegetarian Japanese curry. Instant sub and looking forward to enjoying way more of these…

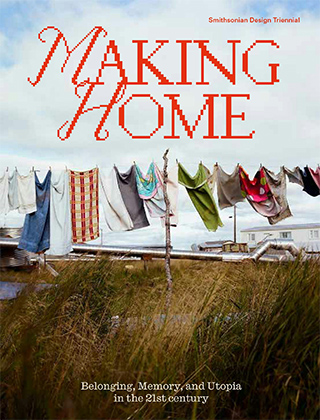

Roxane Gay: Intentional, Home

For too long, I yearned to feel less like a stranger in a strange land and more like someone who is, finally, home. Via MIT Press Reader

When I earned a faculty position at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, I was thrilled. For the previous four years, I had lived in a very small town in eastern Illinois and for the five years before that I had lived in a very small town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. My entire adult life, my geographic circumstances had been dictated by professional urgencies.

In each place, I had an apartment that was mostly fine. I had small circles of wonderful friends. But I had never felt at home — the remoteness, the isolation, and being one of very few people of color made that all but impossible. Lafayette was going to be different, I told myself. With a population of more than 100,000, the town felt positively cosmopolitan. There would be, I hoped, a lot more to do, places to go, the ability to live more than an imitation of life.

Even with all that Lafayette promised, I was determined not to live there but in Indianapolis. It’s not that Indianapolis is paradise, but it is a lovely city. It has a reasonably diverse population. I found a gorgeous, brand-new apartment across from a fancy mall near the interstate. Getting to work would be easy, a straight shot down I-65, less than an hour commute. I was going to have access to shopping and interesting restaurants and interesting people. I would buy my first real adult furniture from a store other than IKEA. Maybe I’d fire up the dating apps and have some measure of a social life. If I was lucky, I would find community. Things were looking up.

I am originally from Omaha, Nebraska, so I am no stranger to living in small towns. But as I’ve gotten older, my tolerance for isolation has diminished. I have spent too many years living in the middle of nowhere. Anything is tolerable for a finite amount of time, but after spending most of my adulthood living and working in the middle of nowhere, I had reached my limit. I didn’t want to have to drive hours to the nearest airport. I didn’t want to have to drive hours or, worse, fly to a city where I can get my hair done. I no longer wanted to feel like an object of curiosity simply by virtue of my race. I was done with quietly seething while tolerating bewildering acts of racism. I was tired of feeling out of place. For too long, I had yearned for something different. I had yearned to feel less like a stranger in a strange land and more like someone who is, finally, home.

It was Central Indiana, a place where people flew the Confederate flag without irony even though Indiana was never a part of the Confederacy.

In the months before my first semester at Purdue started, as I got to know my new colleagues, mostly via email, they were deeply concerned about my living arrangements. The commute would be difficult, they said. And sometimes the Indiana winters were harsh. As a lifelong Midwesterner, I was not worried. An hour’s drive in the middle of nowhere is nothing at all, and after five years in the Upper Peninsula, where it snows more than 300 inches a year, I was confident I could handle any occasional snowfall that blanketed Central Indiana. In truth, I was salivating over the prospect of living in a place with more than 15,000 residents. Eventually, though, I buckled under the pressure, because I am nothing if not a people pleaser — always to my own detriment.

I ended up withdrawing from the lease on my beautiful new dream apartment and losing my deposit. Instead, I rented an apartment in Lafayette in a weird, creepy building with hallways that looked like they once hosted a series of horrifying unsolved murders. The apartments, though, were newly renovated, and it was a small town, so I had a three-bedroom, two-bath apartment with beautiful hardwood floors. My rent was a modest $1,400, and I consoled myself with the knowledge that a livable city was a mere hour away.

Living in Lafayette would be fine. It would be fine. Instead of driving an hour each way to work, I would have a breezy 10-minute commute across the river to West Lafayette. I would, as in the years prior, have large swaths of time to write. I would get to know my colleagues and maybe make some new friends. I would find my people and be more accessible to my students. I would be fine. It would be fine. It only took a few weeks to realize I had made a horrible mistake.

Lafayette was by no means the smallest town I’d ever lived in. It even had some of the creature comforts that make life a little easier without the liabilities of a big city — a multiplex, a Target, a few decent restaurants, a Starbucks with a drive-thru. But it was also Central Indiana, a place where people flew the Confederate flag without irony even though Indiana was never a part of the Confederacy. Because Indiana is an open-carry state, it was not out of the ordinary to see a man walking around in board shorts and a tank top, a gun holstered at his waist.

And then there were the men driving around in oversized pick-up trucks with “Don’t Tread on Me” flags and Ku Klux Klan imagery. Lafayette was inhospitable and lonely. When I left my apartment, I never felt safe. As a somewhat single Black lesbian, I found few local dating prospects. After a very brief foray on e-Harmony, I gave up on the idea that I might meet Ms. Right or even Ms. Right Now. My colleagues were nice enough, but I didn’t feel like I had or was part of a community. It was overwhelming, at almost 40, to feel like I had no future beyond work. I wondered, not for the first time, if I would ever find home, or if I would ever feel home.

One afternoon I watched a large pickup truck with a massive Confederate flag drive back and forth in front of my apartment building. I lay down in bed and stared at the ceiling and thought, I do not have to live like this. I do not want to live like this. I was grateful for my job. I love teaching and working with students, but I was weary of the unbearable compromise professors, particularly in the humanities, must often make — professional security and satisfaction at the expense of personal joy. A good job was enough until it wasn’t. Choosing to forgo living in Indianapolis was, ultimately, a valuable lesson in learning to trust my instincts and learning to allow myself the pleasure of doing what I want, even if it displeases others.

I am not an impulsive person. In general, I accept the way things are and have an annoying but useful ability to surrender to circumstances that feel unchangeable. There was a small glimmer of potential, though. My best friend lived in Los Angeles. One day, I was browsing flights and discovered that there were a few direct flights there every day from Indianapolis. The prices were fairly reasonable, so I bought a ticket, booked a hotel for a week, and flew west. I had no real plan, which was kind of thrilling. And then I did the same thing the next month, and the one after that. Before long, I was spending at least a week a month in LA.

Each time I stepped off the airplane into the grimy chaos of LAX, I felt more human. These sojourns were my first opportunity to spend a significant amount of time in a sprawling megalopolis. At first, I felt like a country mouse. Everything astonished me — the unfathomable and omnipresent traffic; the vibrant street art in bold, beautiful colors; the Mexican food and generally excellent restaurant scene; the museums; the weird little theater companies putting on weird little shows; the farmers markets with produce that didn’t seem real it was so beautiful. There was so much to do all the time. The weather was exceptional all the time. And, of course, there was the ocean — crystalline blue, stretching as far as the eye could see. That’s how I knew I had found a place where I belonged. I am not a beach person, but still I could appreciate the wonder of all that sand and water.

It was a relief to spend so much time in a very liberal place. More people shared my politics than not. There was a sense that the greater good matters. While there was a significant unhoused population, the city (mostly) didn’t try to hide it, and a lot of good people worked tirelessly to help the most vulnerable people in their communities. We are forced to confront inequality every time we leave the house and, frankly, that’s the way it should be until we figure out how to ensure that everyone has a safe, clean home they can afford, no matter what their financial situation is.

I now realize how much I sacrificed for so long, how I whittled myself into someone who could survive anywhere, making myself believe survival was enough.

It was truly life changing having the ability to be intentional about where I spent the majority of my time. After about a year of hotel stays, I rented an apartment downtown and bought a car. I found the local writing community, made new friends, and had a fun but fairly disastrous relationship with a very lovely woman. Three years later, I bought my first house, something I never imagined I would be able to do, especially in an expensive city like Los Angeles, where people with trust funds or mysterious sources of wealth regularly made all-cash offers over the asking price. I was terrified about making such an adult decision. At the time, I didn’t have a partner or kids or even a pet, all the things we tend to associate with home. It was just me, and as I signed 30 years of my life away, I tried to believe just me was enough.

The new house was perfect. I had space for all my books. I could paint the walls whatever color I wanted. I could hang things and not worry about losing a security deposit. In the backyard, there was a wizened old Japanese maple tree with a canopy of fecund branches covering the yard that I would, eventually, drape in sparkly Christmas lights simply because it made me happy.

Every day I see Black people just living their lives. I see all kinds of people, really. I feel more comfortable in my skin, and it’s beautiful to be in a place where difference is both unremarkable and celebrated. I now realize how much I sacrificed for so long, how I whittled myself into someone who could survive anywhere, making myself believe survival was enough. I know I will never again compromise on having a real home.

After I closed on the house and got the keys, I stood in the empty kitchen and looked around at all the bare walls. It was quiet and echoing because there was nothing in it to absorb the sound. I was going to have to fill all that space, which was somewhat daunting, but I also knew, down to the marrow in my bones, that even if I never brought a single thing into my new house, I was already home.

Roxane Gay is a writer, editor, and professor who splits her time between New York and Los Angeles. She is the author of several books including “Bad Feminist” and “Hunger.” This article is excerpted from the volume “Making Home: Belonging, Memory, and Utopia in the 21st Century,” edited by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, Christina L. De León, and Michelle Joan Wilkinson.

A wild bobcat goes crazy for a cardboard box

If it fits…it sits!

Four Longevity Recipes

By the epic sorceress of yum the Korean Vegan

A boring life, Jennifer Farley

So, my darling child, you say you have a boring life. You get up and move through your day, do what you need to do, go home and go to sleep only to get up and do it all over again. You may have a partner, or not. You may have family that loves you, or not. You have friends that appreciate you for who you are, or not. It all seems quite boring, conventional and repetitive. But wait…

The very act of your waking is a miracle! The ability to move, even the least little bit, is a work of art! Your thinking, reasoning brain is a joy! The fact that you are alive and learning is amazing! Please remember these things when you are feeling low and in desperate need of reassurance. Your purpose is one of incredible power and immense importance. You are needed!

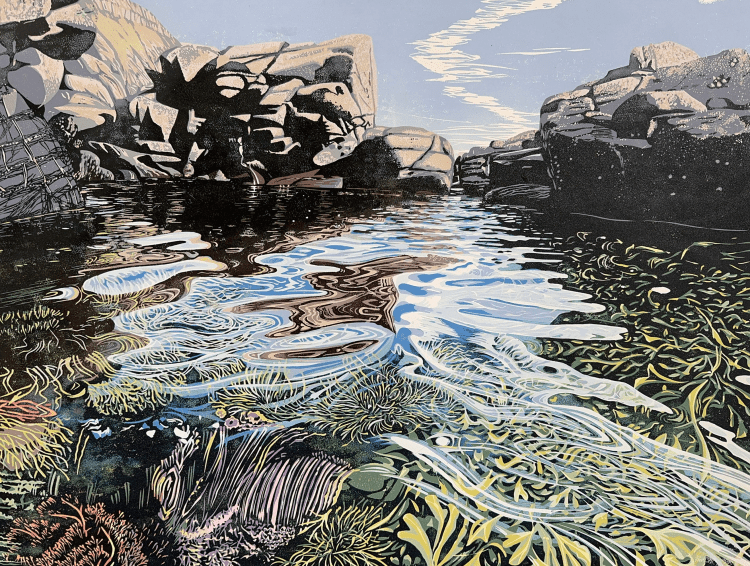

Hazel McNab’s summery exquisite linocuts

Hazel McNab is a Cornish printmaker who captures the wild soul of the outdoors through reduction linocut prints. With a deep love for light, shadow and natural forms, she layers colour and pattern into richly detailed scenes—each print a fleeting moment carved into permanence. Living in Cornwall, her work draws from coastal rhythms and ever-shifting landscapes. Using a single lino block, each cut becomes irreversible, making every edition truly limited. You can find her work at the Riverbank Gallery in Newlyn, at Trelissick House, or by appointment at her home studio. Via Hazel McNab

Did you enjoy this collection? let me know what you think of it below. Thank you for reading my dear friends!

kitty in a box ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person