Prog #rock from #Ukraine, a good #dog’s #retirement, how #apes recognise each other, lessons in fighting tyranny, maps of #lichen in #ambient #music form and much more #InterestingThings #ContentCatnip

Nia Archives BoilerRoom set for International Women’s Day

I love the infectious, energetic Happy Hardcore OG Junglist vibes of this set and the crowd – of all women are totally loving it as well…what is not to love about this! I’ve been listening at least three times already, oh to be there in the room!

Twenty Lessons for Fighting Tyranny

Historian Timothy Snyder suggests ways to defend democracy with individual actions. Although this relates to America, it could be applied to anyone determined to countenance hatred and evil squarely in the face and not look away.

- Do not obey in advance. Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.

- Defend institutions. It is institutions that help us to preserve decency. They need our help as well. Do not speak of “our institutions” unless you make them yours by acting on their behalf. Institutions do not protect themselves. So choose an institution you care about and take its side.

- Beware the one-party state. The parties that remade states and suppressed rivals were not omnipotent from the start. They exploited a historic moment to make political life impossible for their opponents. So support the multiparty system and defend the rules of democratic elections.

- Take responsibility for the face of the world. The symbols of today enable the reality of tomorrow. Notice the swastikas and other signs of hate. Do not look away, and do not get used to them. Remove them yourself and set an example for others to do so.

- Remember professional ethics. When political leaders set a negative example, professional commitments to just practice become important. It is hard to subvert a rule-of-law state without lawyers, or to hold show trials without judges. Authoritarians need obedient civil servants, and concentration camp directors seek businessmen interested in cheap labor.

- Be wary of paramilitaries. When the men with guns who have always claimed to be against the system start wearing uniforms and marching around with torches and pictures of a leader, the end is nigh. When the pro-leader paramilitary and the official police and military intermingle, the end has come.

- Be reflective if you must be armed. If you carry a weapon in public service, God bless you and keep you. But know that evils of the past involved policemen and soldiers finding themselves, one day, doing irregular things. Be ready to say no.

- Stand out. Someone has to. It is easy to follow along. It can feel strange to do or say something different. But without that unease, there is no freedom. Remember Rosa Parks. The moment you set an example, the spell of the status quo is broken, and others will follow.

- Be kind to our language. Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking, even if only to convey that thing you think everyone is saying. Make an effort to separate yourself from the Internet. Read books.

- Believe in truth. To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights.

- Investigate. Figure things out for yourself. Spend more time with long articles. Subsidize investigative journalism by subscribing to print media. Realize that some of what is on the Internet is there to harm you. Learn about sites that investigate propaganda campaigns (some of which come from abroad). Take responsibility for what you communicate to others.

- Make eye contact and small talk. This is not just polite. It is part of being a citizen and a responsible member of society. It is also a way to stay in touch with your surroundings, break down social barriers, and understand whom you should and should not trust. If we enter a culture of denunciation, you will want to know the psychological landscape of your daily life.

- Practice corporeal politics. Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.

- Establish a private life. Nastier rulers will use what they know about you to push you around. Scrub your computer of malware. Remember that email is skywriting. Consider using alternative forms of the Internet, or simply using it less. Have personal exchanges in person. For the same reason, resolve any legal trouble.

- Contribute to good causes. Be active in organizations, political or not, that express your own view of life. Pick a charity or two and set up autopay.

- Learn from peers in other countries. Keep up your friendships abroad, or make new friends abroad. The present difficulties in the United States are an element of a larger trend. And no country is going to find a solution by itself. Make sure you and your family have passports.

- Listen for dangerous words. Be alert to the use of the words extremism and terrorism. Be alive to the fatal notions of emergency and exception. Be angry about the treacherous use of patriotic vocabulary.

- Be calm when the unthinkable arrives. Modern tyranny is terror management. When the terrorist attack comes, remember that authoritarians exploit such events in order to consolidate power. Do not fall for it.

- Be a patriot. Set a good example of what America means for the generations to come.

- Be as courageous as you can. If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die under tyranny.

From the book On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Timothy Snyder. Found at Carnegie

New EP by Opossum is out and it’s a bit of a droning monotone sound

Vakula: New Age Ambient Shamanism from Ukraine

Rex who spent his early years as a detection dog gets a tennis ball celebration for his retirement

Good boi!

Great apes recognise family members after decades

New research finds that great apes: bonobos and chimpanzees have long term memory. A bonobo recognised her sister after 26 years of separation. Animals have lives and MUST be respected #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife

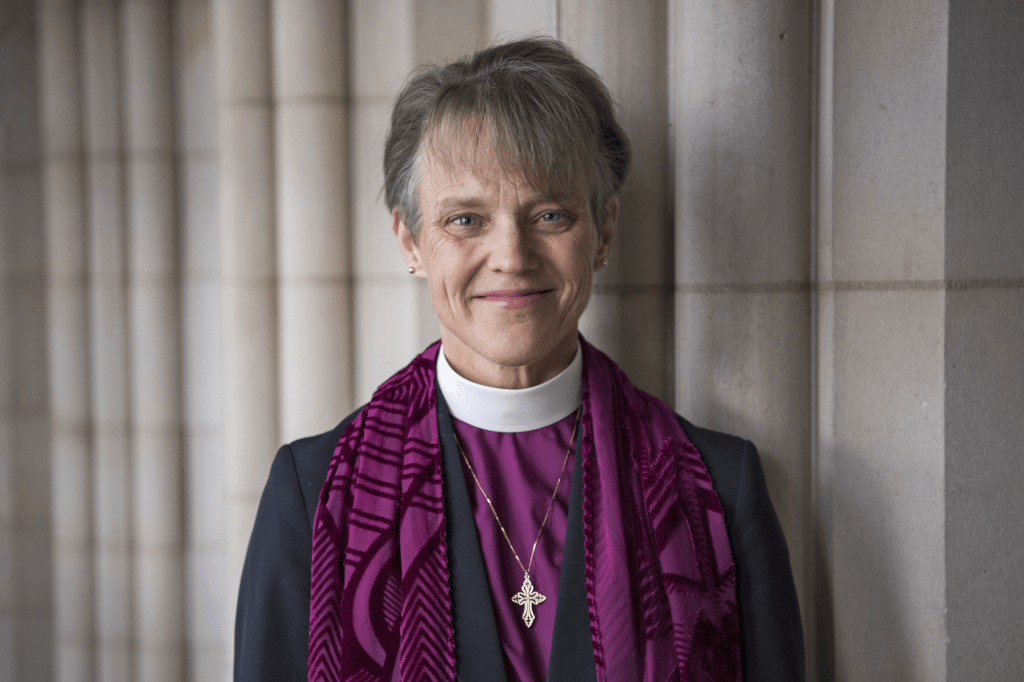

Speech by Mariann Edgar Budde: Episcopal bishop of Washington to Donald Trump

Although I don’t consider myself a Christian, I had a Christian early education and deep understand the teachings of Jesus. I also deeply understand what he meant by being merciful and loving to the poor and those who are marginalised and forgotten. The hatred spewed out by Trump government is an example of the opposite of the teachings of Jesus. The words of Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde below reproduced by the Guardian really chimed well for my own understanding of what Christianity means – it is inclusive, accepting and loving and it respectfully seeks to understand difference, it is not filled with hate. The Bishop of Washington’s sermon at the inauguration of Trump called for love and connection over hatred. The speech was brave and kind – she is an example of the best that Christianity has to offer. She drew the ire of Trump’s supporters because she called for mercy and understanding for the marginalised. Here’s her speech in full, I hope it goes down in history as one of the greatest speeches ever made like Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a Dream,’ it has a similar timeless majesty to it.

O God, you made us in your own image and redeemed us through Jesus your Son: Look with compassion on the whole human family; take away the arrogance and hatred which infect our hearts; break down the walls that separate us; unite us in bonds of love; and work through our struggle and confusion to accomplish your purposes on Earth; that, in your good time, all nations and races may serve you in harmony around your heavenly throne; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Jesus said, “Everyone then who hears these words of mine and acts on them will be like a wise man who built his house on rock. The rain fell, the floods came, and the winds blew and beat on that house, but it did not fall, because it had been founded on rock. And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not act on them will be like a foolish man who built his house on sand. The rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell – and great was its fall!” Now when Jesus had finished saying these things, the crowds were astounded at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority, and not as their scribes.

– Matthew 7:24-29

Joined by many across the country, we have gathered this morning to pray for unity as a nation – not for agreement, political or otherwise, but for the kind of unity that fosters community across diversity and division, a unity that serves the common good.

Unity, in this sense, is the threshold requirement for people to live together in a free society, it is the solid rock, as Jesus said, in this case upon which to build a nation. It is not conformity. It is not a victory of one over another. It is not weary politeness nor passivity born of exhaustion. Unity is not partisan.

Rather, unity is a way of being with one another that encompasses and respects differences, that teaches us to hold multiple perspectives and life experiences as valid and worthy of respect; that enables us, in our communities and in the halls of power, to genuinely care for one another even when we disagree. Those across our country who dedicate their lives, or who volunteer, to help others in times of natural disaster, often at great risk to themselves, never ask those they are helping for whom they voted in the past election or what positions they hold on a particular issue. We are at our best when we follow their example.

Unity at times, is sacrificial, in the way that love is sacrificial, a giving of ourselves for the sake of another. Jesus of Nazareth, in his Sermon on the Mount, exhorts us to love not only our neighbors, but to love our enemies, and to pray for those who persecute us; to be merciful, as our God is merciful, and to forgive others, as God forgives us. Jesus went out of his way to welcome those whom his society deemed as outcasts.

Now I grant you that unity, in this broad, expansive sense, is aspirational, and it’s a lot to pray for – a big ask of our God, worthy of the best of who we are and can be. But there isn’t much to be gained by our prayers if we act in ways that further deepen and exploit the divisions among us. Our Scriptures are quite clear that God is never impressed with prayers when actions are not informed by them. Nor does God spare us from the consequences of our deeds, which, in the end, matter more than the words we pray.

Those of us gathered here in this Cathedral are not naive about the realities of politics. When power, wealth and competing interests are at stake; when views of what America should be are in conflict; when there are strong opinions across a spectrum of possibilities and starkly different understandings of what the right course of action is, there will be winners and losers when votes are cast or decisions made that set the course of public policy and the prioritization of resources. It goes without saying that in a democracy, not everyone’s particular hopes and dreams will be realized in a given legislative session or a presidential term or even a generation. Not everyone’s specific prayers – for those of us who are people of prayer – will be answered as we would like. But for some, the loss of their hopes and dreams will be far more than political defeat, but instead a loss of equality, dignity, and livelihood.

Given this, is true unity among us even possible? And why should we care about it?

Well, I hope that we care, because the culture of contempt that has become normalized in our country threatens to destroy us. We are all bombarded daily with messages from what sociologists now call “the outrage industrial complex”, some of it driven by external forces whose interests are furthered by a polarized America. Contempt fuels our political campaigns and social media, and many profit from it. But it’s a dangerous way to lead a country.

I am a person of faith, and with God’s help I believe that unity in this country is possible – not perfectly, for we are imperfect people and an imperfect union – but sufficient enough to keep us believing in and working to realize the ideals of the United States of America – ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence, with its assertion of innate human equality and dignity.

And we are right to pray for God’s help as we seek unity, for we need God’s help, but only if we ourselves are willing to tend to the foundations upon which unity depends. Like Jesus’ analogy of building a house of faith on the rock of his teachings, as opposed to building a house on sand, the foundations we need for unity must be sturdy enough to withstand the many storms that threaten it.

What are the foundations of unity? Drawing from our sacred traditions and texts, let me suggest that there are at least three.

The first foundation for unity is honoring the inherent dignity of every human being, which is, as all faiths represented here affirm, the birthright of all people as children of the One God. In public discourse, honoring each other’s dignity means refusing to mock, discount, or demonize those with whom we differ, choosing instead to respectfully debate across our differences, and whenever possible, to seek common ground. If common ground is not possible, dignity demands that we remain true to our convictions without contempt for those who hold convictions of their own.

A second foundation for unity is honesty in both private conversation and public discourse. If we aren’t willing to be honest, there is no use in praying for unity, because our actions work against the prayers themselves. We might, for a time, experience a false sense of unity among some, but not the sturdier, broader unity that we need to address the challenges we face.

Now to be fair, we don’t always know where the truth lies, and there is a lot working against the truth now, staggeringly so. But when we do know what is true, it’s incumbent upon us to speak the truth, even when – and especially when – it costs us.

A third foundation for unity is humility, which we all need, because we are all fallible human beings. We make mistakes. We say and do things that we regret. We have our blind spots and biases, and we are perhaps the most dangerous to ourselves and others when we are persuaded, without a doubt, that we are absolutely right and someone else is absolutely wrong. Because then we are just a few steps away from labeling ourselves as the good people, versus the bad people.

The truth is that we are all people, capable of both good and bad. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn astutely observed that “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties, but right through every human heart and through all human hearts.” The more we realize this, the more room we have within ourselves for humility, and openness to one another across our differences, because in fact, we are more like one another than we realize, and we need each other.

Unity is relatively easy to pray for on occasions of solemnity. It’s a lot harder to realize when we’re dealing with real differences in the public arena. But without unity, we are building our nation’s house on sand.

With a commitment to unity that incorporates diversity and transcends disagreement, and the solid foundations of dignity, honesty, and humility that such unity requires, we can do our part, in our time, to help realize the ideals and the dream of America.

Let me make one final plea, Mr President. Millions have put their trust in you. As you told the nation yesterday, you have felt the providential hand of a loving God. In the name of our God, I ask you to have mercy upon the people in our country who are scared now. There are gay, lesbian and transgender children in Democratic, Republican and independent families who fear for their lives.

And the people who pick our crops and clean our office buildings; who labor in our poultry farms and meat-packing plants; who wash the dishes after we eat in restaurants and work the night shift in hospitals – they may not be citizens or have the proper documentation, but the vast majority of immigrants are not criminals. They pay taxes, and are good neighbors. They are faithful members of our churches, mosques and synagogues, gurdwara, and temples.

Have mercy, Mr President, on those in our communities whose children fear that their parents will be taken away. Help those who are fleeing war zones and persecution in their own lands to find compassion and welcome here. Our God teaches us that we are to be merciful to the stranger, for we were once strangers in this land.

May God grant us all the strength and courage to honor the dignity of every human being, speak the truth in love, and walk humbly with one another and our God, for the good of all the people of this nation and the world.

A cool guide about the four types of trauma responses

Found via Cool Guides on Reddit

Odyssey by Carl Jung

I am an orphan, alone; nevertheless, I am found everywhere. I am one but opposed to myself. I am a youth and an old man at one and the same time. I have known neither father nor mother because I have had to be fetched out of the deep like a fish or fell like a white stone from heaven. In woods and mountains, I roam, but I am hidden in the innermost soul of man. I am mortal for everyone, yet I am not touched by the cycle of aeons.

C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, p.227. (Bollingen Tower)

As quoted in the amazing and always insightful blog about spirituality, depth psychology and more by my friend Aladin/ Lamp Magician.

Red rice with roasted mushroom and garlicky cavolo nero

Yummy!

Lichen Maps by Greenhouse

A spacey, new-agey ambient journey that sounds and looks like a love letter to plants…the entire album is good and so are all other Greenhouse albums.

Super cosy houseboat tour

I love the idea of having a houseboat. The owner has used a lot of amazing ideas here. Stripped it back to bare wood, used vibrant mid-century furniture and used sibgle bed mattresses instead of sofas in a sunken loungeroom. All of this seems hugely cosy to me. I hope to do this in my own home eventually.

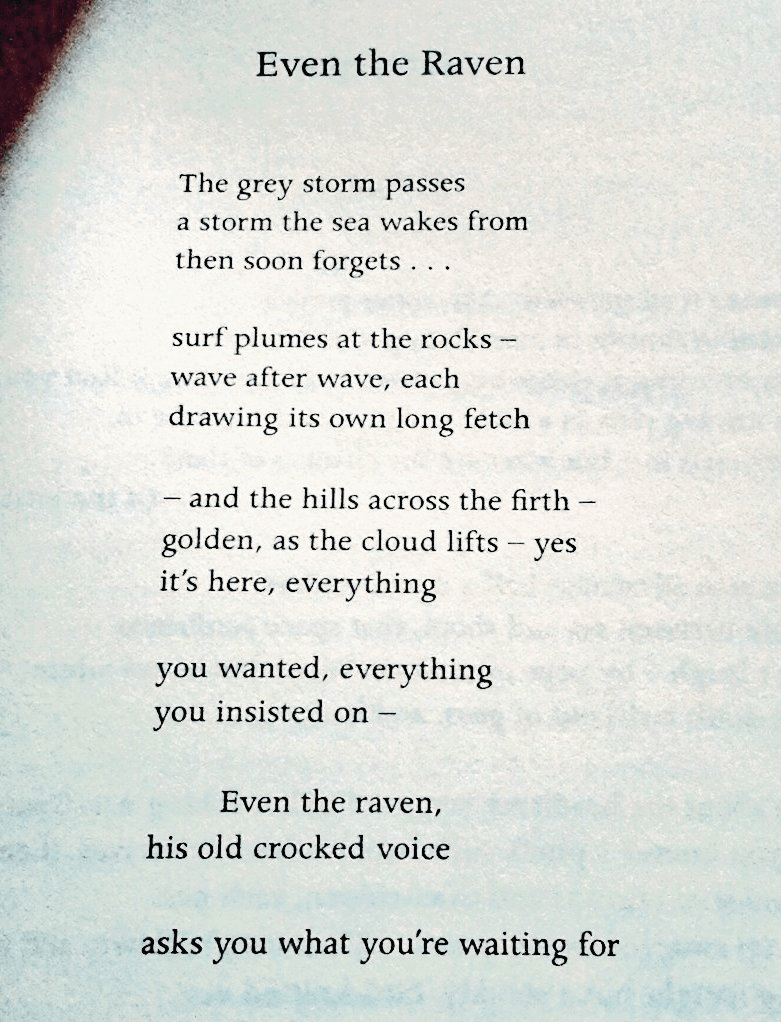

Even the Raven by Kathleen Jamie

The 18th-Century Quaker Dwarf Who Challenged Slavery, Meat-Eating, and Racism

By Natasha Frost for Atlas Obscura

This 1790 portrait of Benjamin Lay, by William Williams and his apprentice, depicts Lay in front of his cave. The basket of vegetables beside him is a hint of his vegetarianism. Public Domain.

One Sunday, 18th-century Quakers living in Abington, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, were met with a strange sight outside their morning meeting. The snow lay thick on the ground and there was Benjamin Lay, a member of the congregation, wearing little clothing, with his “right leg and foot uncovered,” almost knee-deep in the snow. When one Quaker after the next told him that he would get sick or that he should get inside and cover up, he turned to them. “Ah,” he said, “you pretend compassion for me, but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half-clad.”

Lay always cut a striking figure. An 1818 article, republished in the newspaper The Friend in 1911, many years after his death, described him thus:

… only four foot seven in height; his head was large in proportion to his body, the features of his face were remarkable … He was hunch-backed, with a projecting chest, below which his body become much contracted. His legs were so slender, as to appear almost unequal to the purpose of supporting him.

His act of protest in the snow is of the sort that might make the news today, but in the 1730s it would have been radical almost beyond understanding. This was a time, writes Marcus Rediker in his book The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf Who Became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist, when “slavery seemed to many people around the world as natural and unchangeable as the sun, the moon, and the stars in the heavens.” Lay was an abolitionist, vegetarian, pacifist, gender-conscious, anti-capitalist, environmentalist Quaker, with dwarfism and a hunchback, and he wanted to change the apparently “natural” order of things.

This 18th-century painting, by William Jackson, shows a slave ship of the sort Lay began to hear about on his travels. Hearing about their mistreatment seems to have sown an early abolitionist seed. Public Domain.

Despite his ultra-radical leanings, Lay has been almost entirely excised from modern history books. “The wildness of his methods of approaching antislavery is part of it,” Rediker says. “He was extremely militant and completely uncompromising.” This level of abolitionist militance was unprecedented, and only began to become common after the 1830s. Lay sits outside of the standard narrative of the movement, and his disability and lower socioeconomic status make him difficult to place in a clear historical model. “He just didn’t fit the story,” Rediker says.

The snow protest was by no means Lay’s only performed, dramatic, nonviolent act of radicalism. Quaker neighbors of his kept a young “negro girl” as a slave, and continued to justify the practice, even in the face of his exhortations on both the evil of slavery in general and the “wickedness” of separating enslaved children from their parents. When the neighbors refused to listen, Lay invited their six-year-old son into the cave where he lived and innocently entertained him throughout the day. The boy’s parents panicked. The Village Record, a local newspaper, later described how Lay “observed the father and mother running towards his dwelling; as they drew near, discovering their distress, he advanced and met them, enquiring in a feeling manner: ‘What is the matter?’” The parents, understandably terrified, explained that the boy had been missing all day. Lay is said to have paused, and said: “Your child is safe in my house, and you may now conceive of the sorrow you inflict upon the parents of the negro girl you hold in slavery, for she was torn from them by avarice.” Taking the Bible as his model, he seems to have generated living parables to show people the evil of their ways. (Another version of this story claims that the child was a three-year-old girl.)

This 17th-century map shows the island of Barbados as Benjamin and Sarah Lay would have known it. Public Domain.

Lay seems to have had big dreams and ideals to match. Born to a family of common Quakers in Colchester, England, he left his work as a glover at 21, eschewed his likely inheritance, and went to London in pursuit of his fortune. There he became a sailor, desperate to see the world despite the risk of injury or death. (That year, 1703, as many as 10,000 British sailors and crew members lost their lives in a major cyclone.) For more than a decade at sea, he slept in a hammock and lived among people of all ethnicities, shapes, and sizes. For the rest of his life, even after years on land, Lay thought of himself in some sense as a sailor. “At the end of his life,” writes Rediker, “he made a request that shocked his friends and acquaintances: he asked a man to ‘burn his body, and throw the ashes into the sea.’”

It was on his voyages that Lay first became aware of slavery. Fellow sailors told him horror stories about working in the African slave trade, where hundreds of thousands died in transit. Still a devout Quaker, Lay began to connect these practices to Biblical verses about racial equality—that God “hath made of one Blood all Nations of Men for to dwell on all the Face of the Earth.” He soon concluded that slave traders were murderers, and that the practice was barbarous.

An 18th-century engraving shows the ordinary proceedings of Quaker meeting houses. These were often Lay’s sites of choice for protest. Public Domain.

In time, Lay married. Like him, his wife Sarah was a Quaker. She had similar physical conditions, and shared many of his forward-thinking beliefs. The Lays moved, in 1718, to Barbados, a place with some vestiges of a Quaker community. They were appalled to find themselves on an island built on slavery, “barbary and ill-gotten gains,” where slaves were treated worse than horses. The Lays held open meetings and offered meals to the island’s enslaved population, which drew the opprobrium of the island’s white population. Though the Lays had already made plans to leave, these “Masters and Mistresses of Slaves” called for them to be banished. In 1720, they returned to England. Lay was just getting started ruffling feathers in Quaker communities.

Twelve years later they moved to Pennsylvania, where they established themselves in the local Quaker community again. Lay was shocked to find slavery a common practice there, too, after more than a decade in England, where it was rare. At that time, around 10 percent of Pennsylvanians were enslaved, compared with around 90 percent in Barbados. In Pennsylvania, Lay performed some of his most dramatic protest stunts, including disrupting Quaker meetings with abolitionist messages. He is said to have stood up in meetings whenever a slaveholder attempted to speak, and shout: “There’s another negro-master!” Three years later, Sarah died, unexpectedly. Lay was heartbroken.

An 18th-century map shows the Northeast in Benjamin Lay’s time. Public Domain.

By the time he himself died, in 1759, Lay had eked out a strange and deeply principled life for himself in the Philadelphia area. He lived in a cave, made his own clothes, and walked everywhere. He had become a vegetarian and felt that animals, including horses, should not be exploited for their labor or their meat. In 1737 he published the revolutionary tract All Slaveholders That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, a mixture of polemic, musings, and autobiography, put together in a curiously nonlinear, almost postmodern, format. (The publisher—Benjamin Franklin, a longtime, if a little wary, friend—chose to keep his own name off the text.) Despite his requests to be cremated, which would have been tantamount to paganism, Lay was buried in an unmarked grave close to his wife’s, in the Quaker burial ground.

The front page of Lay’s 1737 tract omits the name of his publisher, Benjamin Franklin. Public Domain.

During his life and after his death, many people, Rediker says, thought of Lay as deranged. “[Historians] thought he was not sane, and this was a very effective way of putting him at the margins.” Ableism, too, seems to have factored in this general unwillingness to take him seriously. But some of those in the abolitionist movement did feel the need to celebrate this “Quaker comet,” as he came to be known. Benjamin Rush, one of his earliest biographers, said Lay was known to virtually everyone in Pennsylvania; his curious portrait was said to hang in many Philadelphia homes. This early abolitionist burned bright, and, despite his exclusion from many abolitionist narratives, refuses to be extinguished from history.

Yoshida Hiroshi – Above the Clouds

Yoshida Hiroshi (1876–1950) was a prominent Japanese painter and woodblock printmaker, known for his significant contributions to the shin-hanga movement in early 20th-century Japan. Among his celebrated works is “Above the Clouds,” a euphoric view onto a mountain vista with subtle gradations of light and colour and a spirit of alpine joyfulness.

Did you enjoy this collection? let me know what you think of it below. Thank you for reading my dear friends!

Wow, so many fantastic things you’ve found on the internet! Is it true you’ve made 146 of these? Marvelous! It was nice to read both about the short person becoming vegetarian, the text from that priest to Donald Trump and that long list on how we can/should improve the world and keep democracy.

Thanks a huge bunch for sharing. I’m new here, I’ve been kind of lurking but today I thought I’d come in and say hi!

//Fedora

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Fedora thank you for reading 📚 😊 it’s really nice to meet you and glad you enjoyed these

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too! I look forward to the next one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As always, this collection is captivating, and WOW, how beautifully and profoundly you have illuminated my littleness work. Thank you, my lovely and dear friend, Athena, for your heartfelt honour.

Sending my sincere love and gratitude. 🙏🥰🙏💖

LikeLiked by 1 person